The Cinematic Artistry of Christopher Doyle

Cinematography is the art of storytelling, pivotal in translating a script into a compelling visual narrative. The art form, with its intricate play of camera work, lighting, color palettes, framing, composition, and movement is what shapes the mood, tone, and emotional impact of a film, guiding the audience’s experience and interpretation of the story. By crafting the visual language through which a story is told, cinematography can elevate the narrative, making it resonate on a deeper level and leaving a lasting impression on the viewers. Within this realm, few cinematographers have managed to imprint their unique visual style onto the canvas of international cinema as indelibly as Christopher Doyle. Known for his visually arresting and vibrant work, Doyle has contributed to some of the most memorable films over the past few decades, earning himself a spot amongst the greats in modern cinematography.

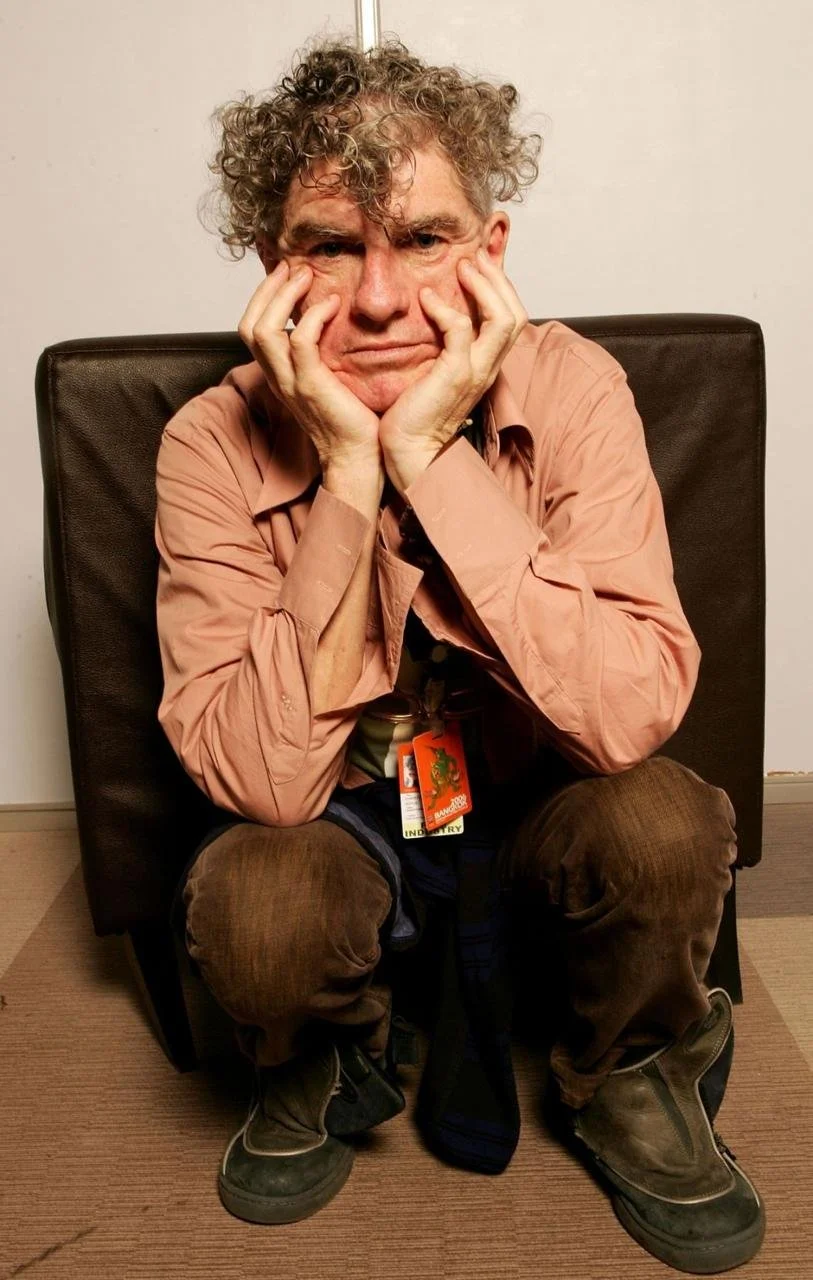

Christopher Doyle, born in 1952 in Sydney, Australia, initially began his career in the medical field. In his early twenties, he left his homeland and embarked on a journey that would distance him far from his original career path. Doyle's time abroad was marked by a variety of unconventional jobs, ranging from working as an oil driller in India to herding cows in Israel, and even practicing Chinese medicine in Thailand. Eventually, Doyle made his way to Hong Kong in the late 1970s, a move that proved pivotal in his career. After studying Mandarin at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where he was given the name “Du Kefeng” — meaning “like the wind,” Doyle discovered his passion for film. His initial exploration into photography in Taiwan paved the way into the film industry. Together with director Edward Yang he collaborated on and gave birth to the film "That Day, on the Beach" (1983), marking the beginning of Doyle's career in film.

“I didn’t start making films until I was 34. But that wasted youth was probably the most valuable asset for what I’m doing now. You see the world, you end up in jail three or four times, you accumulate experience. And it gives you something to say. If you don’t have anything to say then you shouldn’t be making films. It’s nothing to do with what lens you’re using”

Hong Kong, known for its dynamic street life and distinct urban scenery, became the perfect backdrop for Doyle. The pulsating energy, the glow of neon lights at night, and the city's eclectic architecture played a significant role in shaping his cinematic vision, capturing the stunning beauty of the city as few have. In Hong Kong, Christopher Doyle met and formed a friendship with film-director Wong Kar-wai, leading to their first film together, "Days of Being Wild" (1990). This film not only established a dynamic partnership but also introduced audiences to a new chapter in cinematic storytelling. Since then, they have created seven movies together, such as "Chungking Express," "Fallen Angels," and "2046." These films, set against the dynamic canvas of Hong Kong's, have emerged as iconic masterpieces, celebrated for their compelling stories and incredible visuals. Doyle's cinematography—marked by vibrant color palettes, intricate play with light and shadow, and fluid camera movements—perfectly complements Wong's thematic exploration. As we delve into some of the works that define their collaboration, we explore not just the evolution of a distinctive cinematic style but also how cinematography can serve as a powerful medium to communicate the emotions and experiences that resonate with us all.

“It is being subjective and objective, it is being engaged and yet standing back and noticing something that perhaps other people didn’t notice before, or celebrating something that you feel is beautiful or valid, or true or engaging in some way”

Days of being wild, 2000

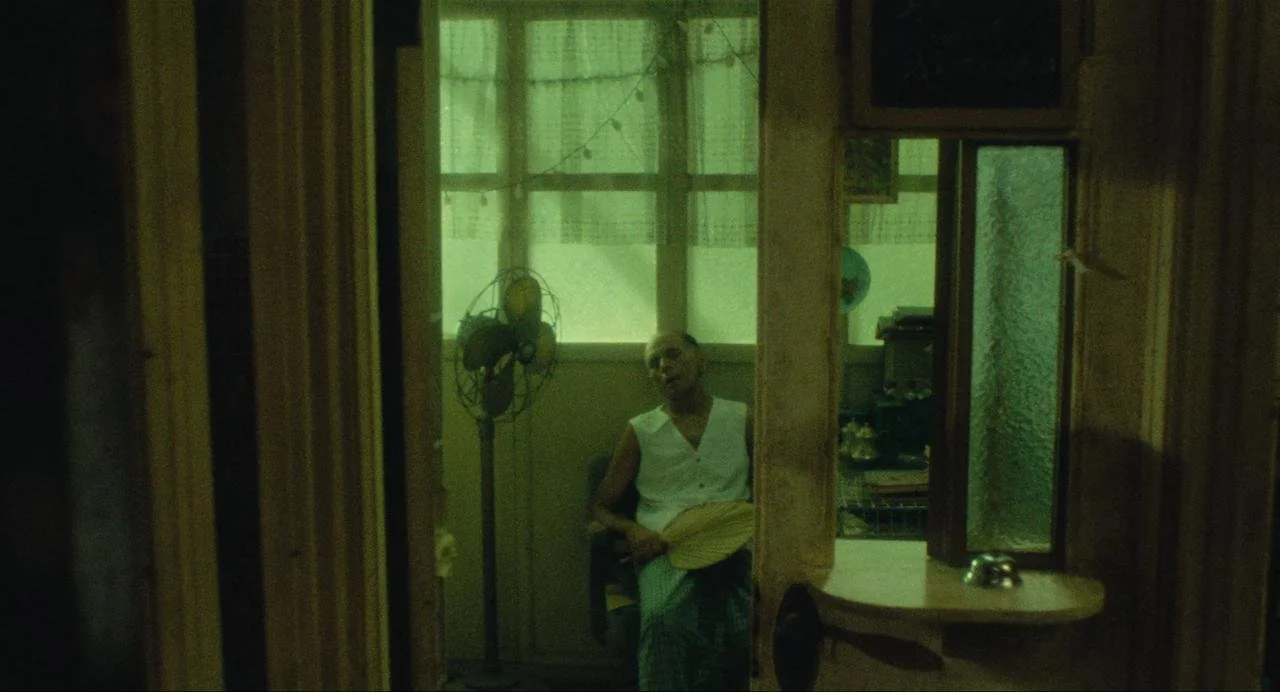

Released in 1990, 'Days of Being Wild' marks the first collaboration between Wong and Doyle, and the first chapter of a celebrated love trilogy, often referred to as the "Love Trilogy." Doyle’s cinematography plays a pivotal role in setting the film's tone, utilizing a rich color palette that aligns seamlessly with its mood and the early 1960s setting. The deliberate choice of hues—shades of blue, green, and yellow—imbues each scene with a sense of nostalgia and longing, effectively transporting us back in time. Particularly notable is the use of green, which dominates the segments set in the lush, tropical landscapes of the Philippines. This choice marks a distinct departure from the neon-lit, kinetic energy of Hong Kong depicted in other collaborations between Doyle and Wong Kar-wai, such as "Fallen Angels" and "Chungking Express." Instead, "Days of Being Wild" offers a visual narrative focused on moments of stillness and reflection. Doyle makes use of intimate framings and close-ups to delve into the characters' emotions, without the need for dialogue. This approach not only showcases Doyle’s mastery of visual storytelling but also highlights the film’s thematic exploration of identity and belonging.

Fallen Angels, 1995

Released in 1995 and celebrated for its visual innovation, 'Fallen Angels' captivates us with its distinctive color palette, which not only enriches the storytelling but also adds a layer of sensory depth to the film. By contrasting cool blues and greens against the warmth of ambers and reds, Doyle creates a visual contrast that reflects the characters' inner conflicts. Doyle's selection of colors is always carefully orchestrated, with one of his key techniques being the use of complementary color schemes throughout most of the scenes in his films – contrasting pairs such as yellow and purple, blue and orange, and green and red. By employing complementary colors, the colors intensify each other, making them appear more vivid and dramatic.

Complementary colors are two colors that are on opposite sides of the color wheel.

Christopher Doyle stretches the visual canvas of the film by utilizing wide-angle lenses, enhancing the film’s emotional narrative. The technique draws us closer to the characters and immerses us in the vivid and colorful chaos of the city surrounding them – it's like being drawn into the film's world and experiencing the characters' emotions and the bustling energy of the city.

Fallen Angels, 1995

Adhering to a predominantly one-source lighting technique, he creates an emotional intensity to the characters and scenes. With shadows and light playing across the actors' faces, adding depth and feeling to each frame. Whether it is a dim lamp, cool white fluorescents or the vibrant glow of a neon streetlight, all work to sculpt the characters sharply against their surroundings. The chiaroscuro lighting technique generates dramatic contrasting deep shadows and light, highlighting the actors and making them stand out, enhancing the drama of the scene.

IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE

The second part of the love trilogy, "In the Mood for Love" (2000) is a mood piece that explores unrequited love and longing, set in 1960s Hong Kong. With its minimal dialogue, the audience's attention is naturally drawn towards the film's visuals, inviting viewers to pay attention to subtle expressions and details that convey the story's depth. The film immerses viewers in a palette of saturated warm colors, with a dominance of deep reds, warm earthy tones, and subdued blues and greens. These colors not only beautifully evoke the time period but also reflect the film's central themes of romance and suppressed emotions. The film is known for its use of slow-motion and close-ups that capture the subtle nuances of the characters’ repressed emotions and the sensuality of their unspoken desires. Wong has described the film as “two people dancing together slowly.” Even as the film portrays the innocent relationship between Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan, we can sense a relationship that is beyond mere friendship. Through Doyle's cinematography, the movie is enveloped with a seductive and sensual aura, achieved without relying on words or explicit scenes. The visual storytelling alone conveys the depth and complexity of their connection, showcasing how powerful imagery can articulate the unspoken tensions and desires between characters.

In the Mood for Love, 2000

Doyle's cinematography in each of his films is far from just a visually beautiful aesthetic; it embodies a deeply intentional artistry where every element— from the nuanced color palette to the choice of lenses, from the source and quality of lighting to the composition of each frame—is carefully chosen to encapsulate the human experience in its rawest form. This deliberate craftsmanship extends beyond creating mere scenes; it builds atmospheres, evokes emotions, and tells stories in ways words alone cannot. Doyle's approach to cinematography challenges the viewer to see cinema not just as a medium of entertainment but as a complex language of visual poetry. He redefines the boundaries of cinematic expression, proving that the essence of film lies not only in its ability to tell stories but in its capacity to make us feel deeply, think profoundly, and view the world through a lens that captures both beauty and tragedy. Through his visionary work, Doyle reminds us that in cinema, as in life, it is the nuances and the unspoken that often hold the deepest meaning.

“I’m very proud of the many films I made, but I cannot be self-satisfied. I usually say the next film is my best one ”